Massage Therapy and Body Image

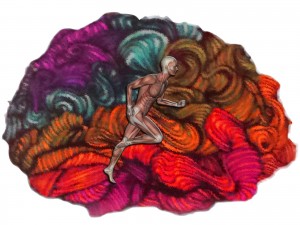

Body image or the conscious sense of our body, is our perception of and beliefs about our own body’s appearance. Or simply the feeling we have of our own body. Constructed by the brain from past experience and present sensations, the body image is a mental representation of our physical appearance and is a fundamental aspect of self-awareness and self-identity. Body image depends on our internal ‘body maps’ that are modulated by somatic and proprioceptive input.

The term “body image” was introduced in 1935 by Paul Schilder, an Austrian-American neurologist, which refers to the mental pictures we have of our bodies or the way our bodies appear to us. It is the set of beliefs we hold about ourselves. The topic of body image is covered extensively in recent popular books: The Body has A Mind of Its Own by Sandra and Matthew Blakeslee and The Brain that Changes Itself by Norman Doidge. Distorted body image Body image can be disrupted in people with pain disorders, and the disruption can have profound physical and psychological effects. For example, body image distortion is implicated in people with eating disorders (such as anorexia nervosa). Anorexics experience their bodies as fat even when they are on the edge of starvation.

Body image can be distorted in people suffering from chronic pain, as complex regional pain syndrome, phantom limb pain, and back pain. Pain is commonly experienced as projected into the body. People say “My back is killing me!”, but not “My pain is killing me.” However, people having phantom limb pain show that we don’t need a body part or even pain receptors to feel pain. The only factor that controls this pain is our body image. Physician VS Ramachandran said that pain is an opinion on the organism’s state of health rather than a mere reflexive response to injury. The brain gathers evidence from many sources before triggering pain. Pain, like the body image, is a construct of our brain. Therefore he successfully used a mirror box to modify a body image and eliminate the phantom and its pain.

Dr. Lorimer Mosely, a scientist from Australia, have demonstrated visual distortions of the body image in patients suffering from chronic pain can significantly affect their perception of painful sensations. People with CRPS and phantom limb pain were shown to have decreased tactile acuity and distorted body image for the affected limb. CRPS and phantom limb pain patients tend to perceive the painful or phantom limb as being bigger than it really is. Lorimer also tested to use the mirror box to make chronic pain in a real limb disappear. He asked his patients to simply imagine moving their painful limbs, without executing the movements, in order to activate brain networks for movement. The patients also looked at pictures of hands, to determine whether they were the left or right until they could identify them quickly and accurately. They were shown hands in various positions and asked to imagine them for fifteen minutes, three times a day. After practicing the visualization exercises they did the mirror therapy, and with twelve weeks of therapy, pain had diminished in some and had disappeared in half. Lorimer also demonstrated that people with chronic back pain has disrupted body image. The patients were unable to clearly delineate the outline of their trunk and stated that they could not ‘‘find it”. This finding raises the possibility that training body image or tactile acuity may help patients in chronic spinal pain.

Massage is well known to make people feel more relaxed and better about themselves. While there are many evidences that suggest positive effects of massage on psychological health, several studies now showed the positive effects of massage on body image. Researchers have started to investigate massage as a way of improving body image. Thomas Pruzinsky in his book Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice, writes that massage therapy is a somatic approach that is helpful in positively affecting body image “by helping the client reconnect to the body in a very concrete manner.” Dr. Marcia Hutchinson, the author of the book Transforming Body Image, suggested that since body image is a product of the imagination, it can also be changed using the imagination. Hutchinson describes an exercise called “imaginal massage” in which you visualize massage occurring allowing the hands of the massage therapist to transfer healing to your bodymind allowing acceptance of your body.

A study conducted by the Department of Nursing, Wonkwang Health Science College in South Korea evaluated the effect of massage on abdominal fat, waist circumference and body image of post-menopausal women. The participants received a full body massage once a week and massaged their own abdomens twice a day during a six-week experiment. Half the group received massages with grapeseed oil. The other half received an aromatherapy massage with a blend of essential oils. Both groups felt better and improved body image after the treatment, but the group receiving aromatherapy massage showed significant changes across all areas – body image, waist circumference and abdominal fat.

An in-depth interviews study conducted by Mary Bredin in UK explored the experiences of breast loss in mastectomy with particular focus on body image issues in three women. A pilot study also investigated a massage intervention as a means of helping them adjust to living with their changed body image. The study showed that the availability of a body-centered therapy such as massage might help with certain aspects of life adjustment.

The Touch Research Institute in Miami studied the effect of massage on people with eating disorders including bulimia (overeating and vomiting) and anorexia. Body image dissatisfaction contributes to the development and maintenance of these eating disorders. Adolescents with bulimia who received one month of twice weekly massages plus their standard daily group therapy treatment (versus adolescents with bulimia who only received the standard group therapy) had fewer symptoms of depression, lower anxiety levels, and lower stress hormone levels (urinary cortisol levels). Their eating habits also improved, and their

body image was less distorted. In another study on adolescents with anorexia at the same hospital the massaged women (versus the standard group therapy control women) reported lower anxiety levels and had lower stress hormone levels.Over the five-week treatment period, they also reported decreases in body dissatisfaction on the Eating Disorder Inventory and showed increased dopamine and norepinephrine levels.

Massage may improve body image by decreasing negative body image and increasing positive body image. A positive body image accepts the body and respects it by attending to its needs and engaging in healthy behaviours. In a qualitative study, many college women with a positive body image indicated that they regularly received massages to take care of, appreciate, and pamper their body, showing that they view massage as pleasurable. Massage treatment could function as a positive feedback cycle, by not only lessening negative feelings about the body through increasing body acceptance, but also by associating emergent positive feelings with the body and partaking in a behaviour that honours and relaxes the body. Massage could also improve body image by reducing women’s objectification of their body. A woman with a negative body image often views her body as an object to be evaluated. Women in western cultures learn to survey their bodies through the eyes of their culture to avoid negative judgment. A woman can feel that her body brings unhappiness and shame because it is perceived as not measuring up to society’s ideals. A woman who receives a massage, can let her body becomes a vehicle for the experience of pleasure. Women who hold a negative body image may avoid massage due to shame or embarrassment.

A study conducted by scientists from Bridgewater State University, MA, USA looked at the effect of massage on state body image. The study recruited forty-nine female university students; they were randomly assigned to either a massage condition or a control condition. It was hypothesized that participants in the massage condition would report improved state body image following the intervention when compared to participants in the control condition. As predicted, participants in the massage condition reported a more favourable state body image than participants in the control condition post-manipulation. Certain body image evaluations were moderately associated with views that massage is pleasurable, with the link between Body Areas Satisfaction and viewing massage as pleasurable reaching significance.

In this study, it is conclusive that the female university students reported feeling better about themselves and their bodies after having massage. Meanwhile the control group, who did not receive massage, showed no change in their attitudes. A woman’s negative view of her body can make the body seem untouchable and grotesque. Massage can be a vehicle to have a positive experience the body could potentially break through these negative body image attitudes. Nevertheless, a woman who holds negative thoughts about her body may be less apt to seek out massage therapy. This attitude will need to be addressed for massage to be a viable therapeutic option. In addition to relaxation and a shift in focus from the body as an object, regular massage could help change negative thoughts about the body as the body becomes associated with the good feelings that it brings through the massage experience.

References

Bredin M. Mastectomy, body image and therapeutic massage: a qualitative study of women’s experience. J Adv Nurs. 1999 May;29(5):1113-20.

Cash TF, Pruzinsky T. Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. Guilford Press, 2004.

Dunigan BJ, King TK, Morse BJ.A preliminary examination of the effect of massage on state body image. Body Image . 2011 8(4):411-4.

Field T, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, Field T, Fierro K, Henteleff T, Mueller C, Yando R, Shaw S, Burman I. Bulimic adolescents benefit from massage therapy. Adolescence. 1998 Fall;33(131):555-63.

Hart S, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Nearing G, Shaw S, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Anorexia nervosa symptoms are reduced by massage therapy.Eat Disord. 2001 Winter;9(4):289-99.

Hutchinson MG. Transforming Body Image: Learning to Love the Body You Have. The Crossing Press, 1985.

Kim HJ. Effect of aromatherapy massage on abdominal fat and body image in post-menopausal women. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2007 Jun;37(4):603-12. [Article in Korean]

Lotze M, Moseley GL. Role of distorted body image in pain. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007 Dec;9(6):488-96.

Moseley GL. I can’t find it! Distorted body image and tactile dysfunction in patients with chronic back pain. Pain. 2008 Nov 15;140(1):239-43.

Wood-Barcalow, N. L., Tylka, T. L., & Augustus- Horvath, C. L. (2010). ’But I like my body’: Positive body image characteristics and a holistic model for young-adult women. Body Image, 7, 106–116.