The Thoracolumbar Fascia: A New Frontier in Low Back Pain Therapy

In recent years, the thoracolumbar fascia (TLF) has become an increasingly important focus in understanding and treating low back pain. Long recognized for its role in trunk stability, new research suggests that the TLF may also play a significant role in the development, persistence, and perception of back pain. For therapists, this opens up new perspectives in both assessment and treatment.

Prof. Robert Schleip recently summarized the recent finding on TLF in an article Alterations of the thoracolumbar fascia in patients with back pain: the chicken or the egg? published in Leitthema

The Anatomy and Role of the TLF

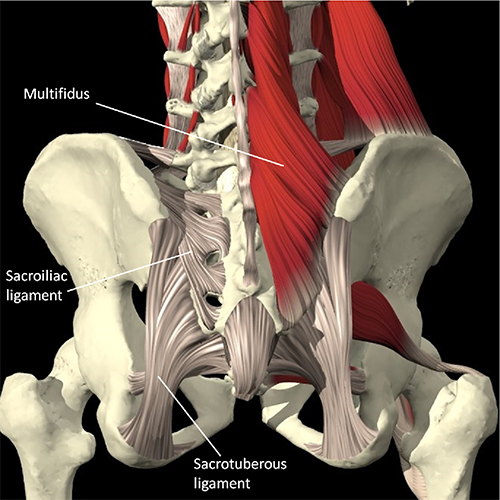

The thoracolumbar fascia is a large, complex sheet of connective tissue stretching from the sacrum up to the cervical spine. It is composed of multiple layers, with the posterior layer being particularly relevant in back pain discussions. This fascial structure is deeply interconnected with surrounding muscles, including the erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, gluteus maximus, and transversus abdominis.

Functionally, the TLF serves several key roles:

- It transfers forces between the trunk and limbs during movement.

- It plays a central part in proprioception and coordination.

- It contributes to overall trunk stability.

Through these mechanisms, the TLF not only supports movement but helps protect the spine from overload. However, when this system is disrupted, problems can emerge.

Nerve Supply and Pain Sensitivity

What makes the TLF particularly interesting in pain research is its rich sensory innervation. Histological studies have shown that the fascia contains numerous free nerve endings, including a high density of nociceptive (pain-sensitive) fibers. In fact, the concentration of these pain receptors is even higher than in nearby muscle tissue.

This dense network of pain-sensitive nerves means that the TLF is highly reactive to mechanical, chemical, or even electrical stimulation. In people with chronic low back pain, the fascia appears to become even more sensitive, potentially contributing to ongoing pain sensations.

Structural Changes in the TLF: What the Research Shows

Several studies have demonstrated that patients with low back pain often exhibit clear structural changes in the TLF.

One consistent finding is fascial thickening. Ultrasound imaging has revealed that the posterior TLF is significantly thicker in men with chronic low back pain compared to healthy controls. This thickening may be due to inflammatory processes or compensatory changes in response to altered mechanical loading.

Another key finding is reduced shear mobility between the layers of the fascia. In both chronic and acute low back pain patients, studies have observed a significant decrease in the ability of the fascial layers to slide over one another during movement. This loss of glide could reflect changes in the extracellular matrix composition or even delayed sympathetic nervous system responses to stress.

Animal studies provide further insights. Research in a pig model showed that even localized fascial injury, combined with limited movement, can lead to both thickening and reduced fascial mobility—not only at the injury site but also in surrounding areas. This suggests that once fascial dysfunction begins, it can affect broader regions of the back, especially if normal movement is restricted.

Changes in Pain Processing: Beyond the Tissue

The structural changes in the TLF are accompanied by alterations in how pain is processed and perceived. Animal studies show that stimulation of the TLF can heighten activity in spinal cord neurons, potentially fueling the development of chronic pain via neuroplastic changes. Moreover, chronic inflammation within the fascia may promote the formation of additional nociceptive nerve endings, further increasing sensitivity.

Human studies using advanced imaging and sensory testing have confirmed that people with chronic low back pain often have heightened sensitivity in the TLF area. This suggests that fascia is not merely a passive tissue but may actively contribute to pain persistence.

Cause or Consequence? A Complex Interaction

A central question remains: are these fascial changes the cause of low back pain, or do they develop as a result of altered movement and pain behaviors? Three possible explanations have been proposed:

- Primary fascial dysfunction: Microtraumas, repetitive strain, or overload may directly trigger structural changes in the fascia, increase nociceptor activity, and initiate chronic pain.

- Secondary adaptation: Changes in the fascia may occur as a consequence of altered movement patterns, guarding, or disuse, serving as a maladaptive response to ongoing pain.

- A bidirectional cycle: Most likely, a complex feedback loop exists. Fascial changes contribute to pain, which then alters movement patterns, leading to further fascial dysfunction—a self-perpetuating vicious cycle.

Clinical Implications for Therapists

For manual therapists, physiotherapists, and other movement professionals, these findings offer important clinical takeaways:

- Assessment: The TLF should be actively evaluated in patients with back pain. Palpation, movement observation, and potentially ultrasound or elastography may help identify fascial restrictions or changes.

-

Treatment Approaches:

- Manual therapy that targets fascial glide and mobility may help restore normal movement between fascial layers.

- Movement-based therapies should include exercises that promote trunk and fascial mobility.

- Newer methods such as shockwave therapy or the Typaldos fascial distortion model may provide additional therapeutic tools targeting fascial dysfunction.

Looking Ahead

Current research strongly supports the importance of the thoracolumbar fascia in both the development and persistence of low back pain. While much remains to be learned—especially regarding whether fascial changes are primarily a cause or consequence—therapists should begin to place greater focus on the fascia in both assessment and treatment.

Ongoing studies, especially those that follow patients over time, will hopefully clarify these complex relationships and lead to even more effective, fascia-informed treatment strategies for chronic low back pain.